Article Source: Fast Company

Article Link: https://www.fastcompany.com/90219684/this-town-will-get-its-heat-from-an-unlikely-source-a-data-center

This town will get its heat from an unlikely source: a data center

In Norway, the new town of Lyseparken is being designed specifically to allow homes and businesses and a central data center to work together to reduce energy usage.

In a new town called Lyseparken, being built from scratch on vacant land near Bergen, Norway, a data center will help heat surrounding businesses–part of a design that could create the world’s first energy-positive city.

“Our first goal was to make a self-sufficient area by using local, renewable resources,” says Fredrik Seliussen, who is leading the project for the local municipality of Os, which wanted to develop the land to bring new jobs to the area. “After we had theoretically solved this . . . we decided to go further to the next level. The goal was not to be carbon neutral–but it might be the result of our business model.”

Data centers are typically built in remote areas because they use so much land; one data center in Nevada sprawls over 7.2 million square feet. But new, smaller data centers can be built in urban areas, reducing the time it takes to transfer data to users and creating a new opportunity to make use of a data center’s other product–an enormous amount of waste heat.

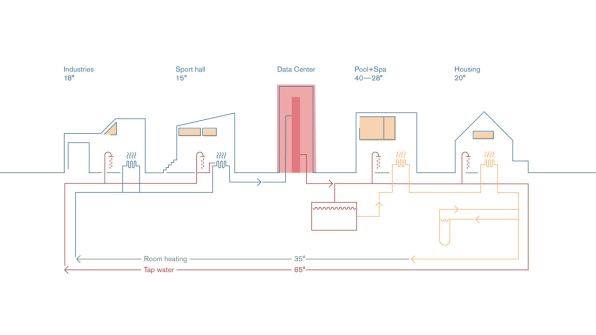

As data centers use energy (globally, they used 416 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2016, more than the entire United Kingdom), one big chunk of that electricity is used to keep servers cool. In the design for the new data center at Lyseparken, instead of fans, a liquid cooling system will send extra heat to a district heating system, which connects to businesses in the area, heating each building via the floor. The liquid loses heat as it travels, so the buildings that need heat most are located closest to the data center. Eventually, the liquid is cool enough that it can loop back to the data center to cool it down–and as that happens, it heats up again to start the process over.In Lyseparken, the data center will sit at the heart of a new business park with 600,000 square meters of office space. The businesses will each have a stake in a local power company, and will each produce and consume electricity from a mix of renewable sources including solar and thermal energy. The data center–which can handle data for businesses or government–will buy solar energy from the power company, and then sell heat back. The arrangement offers low power bills, dividends from the power company for building owners, and, for the data center and other businesses with waste heat, the opportunity to make money from that energy. The new development will also include 3,000-5,000 new houses, which will house people working in the new area. The new town will be close enough to the city of Os that people can bike there.

The data center will first be built as a demo project later this year and then as a pilot expected to be running by 2021, and is the first implementation of a concept called the “Spark” that could be used in any city. It reimagines how the space inside a data center could be used.

“It is a place for human activity and human interaction,” says Rune Veselgard, project manager from Snøhetta, the architecture firm that designed the data center in collaboration with partners. “From being an enormous industrial building in a desolated desert using an unimaginable amount of energy, the data center of the future, the Spark is powering a small city or an entire neighborhood while being the preferred place for people to meet their friends, socialize or do sports, go swimming, or maybe spend an afternoon at the spa. The data center has become something positive for its local community.”

As the town plans for a carbon-neutral future, Seliussen says that the biggest challenge isn’t the technology, but implementing it. “I believe our main challenge is laws and regulations,” he says. “It is not easy to be innovative when all laws are made for the past. In our project, we had to develop new technology that didn’t exist, but we believe we can solve those challenges.”

![[Image: Snøhetta/Plompmozes]](https://images.fastcompany.net/image/upload/w_562)